Pop science: A baking soda volcano sized controversy

March 4, 2022

Nearly all of us remember the glorious days of elementary school, sitting in the science lab as the teacher performed a demonstration of that day’s activity. From discovering viscosity to designing a mentos-activated volcano, these experiments kickstarted a love for science in many children.

Pop science is the type of science commonly displayed on TV, the Internet or written about in newspapers (think Bill Nye or your favorite science YouTuber). These icons use science as a tool to entertain and dazzle their audience with a secondary purpose to teach something new. They pick flashy projects, like making elephant toothpaste or explosions, to draw in a large audience.

As popular as pop science is, it’s commonly looked down upon, seen as “pointless” or “juvenile.” One search online and you will find countless editorials dismissing pop science, decrying it as a poor educational tool that only exists for people to profit off the backs of “actual scientists.”

Miguel A.R.B. Castanho—Professor of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal—wrote a research paper on this very subject, titled “Pop-Science: Facts or Fiction? Friend or Foe?”

The paper, which was written in 2003, focuses on the long-standing turbulent relationship between science and the media. Castanho divides those involved into three categories: the scientist, the public and the middle-man (typically journalists). According to him, the main issue with science journalism is a difference in values. Journalists “value immediate social impact,” but scientists “value scientific soundness” and often cannot provide the solid “yes” or “no” answer that the other party needs.

Because of this desire to have instant impact, the merging of science with the media often has some issues—namely, clickbait. News outlets are encouraged to make flashy headlines to draw the reader’s attention, even if they disregard nuance in the scientific findings. A study may only be applicable to a small group of people, or be poorly run and later debunked without any new reports on the changes.

In 2017, researchers from the scientific journal Peplos One analyzed over 5000 articles written about biomedical studies and found that newspapers very rarely report on subsequent studies when they find null results. This means that false information typically continues to spread even after it is disproven due to misreporting and a subsequent lack of coverage.

Not all science journalism suffers from these issues, though. Robert Sanders, a transportation journalist, makes educational videos on his YouTube channel, Road Guy Rob. Sanders creates self-described “silly transportation videos that somebody can hopefully learn something useful about roads from.”

Even though Sanders targets a casual audience, the production of his videos still takes a lot of time. He said, “The amount of work I put into making one of my videos is comparable to writing an undergraduate college term paper. I start off every story by going to Google.”

After his extensive research, Sanders tries to figure out how he can convey this information to his viewers. “With traffic engineering, every single one of us have spent a significant portion of our lives on the road. We’ve all been on the big freeway interchanges, we’ve seen the bridges, we’ve driven cars and ridden in cars so we already have all the scientific knowledge we need in our hands because we’ve experienced it, at least subconsciously. It’s just trying to give some plain English to help people understand. And as you go, you can sneak the scientific terminology in with it.”

He also emphasized the importance of speaking less formally. “Active voice writing, present-tense conversational,” said Sanders. “Speak like a human; don’t speak like an academic journal.”

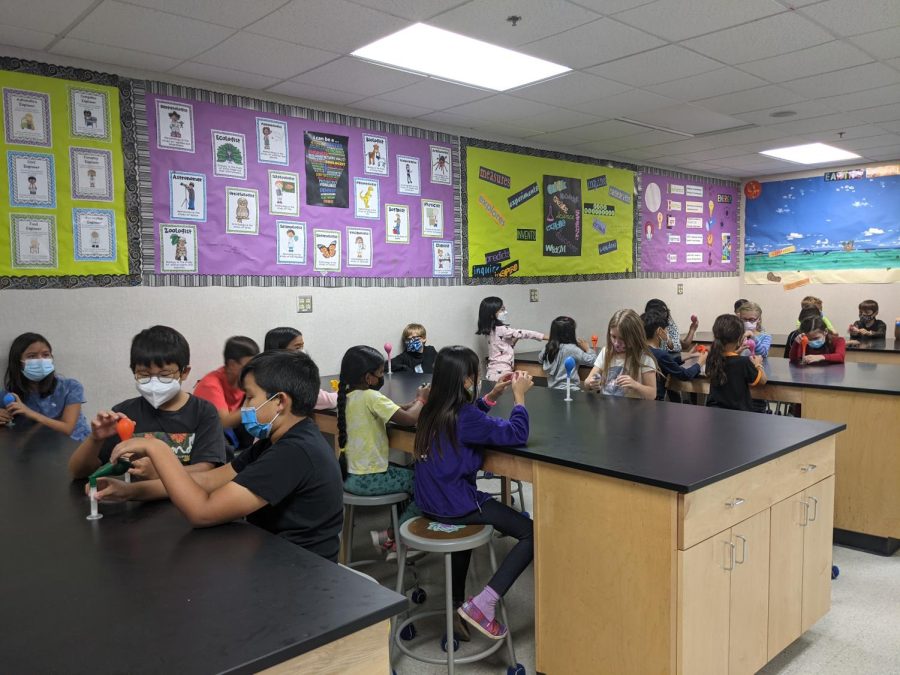

Pop science has also had a profound impact on students at West Ranch. Senior Ethan Ryu is co-president of Target Tutors, a science education club that works on fun projects with local elementary school students to increase their interest in STEM. He shared the amount of thought that goes into the designing of each lesson they teach. “A lot of the time it’s something with food and things that look very colorful,” said Ryu. “They like it a lot, and we try to show them the before and after so that they can see the causes and effects.”

The response he has received from the students has been highly encouraging: “I was a bit worried at first, because I thought that the kids wouldn’t really be that into it. Just recalling myself as an elementary schooler, I felt like maybe I wouldn’t be that into it. But I think their enthusiasm has made it really easy for us to want to come back and keep teaching.”

Though there are many issues with how our society reports on the subject, pop science is still an effective way to draw people into topics they previously had no knowledge of. Reporting on science in an accurate, educational way can be very difficult, but it is vital for creating the next generation of scientists.